While Bordeaux zipped off on the back of a scooter, I retreated with my backpack into a tiny pocket of shade. The line of motorbikes and trucks in front of me growled impatiently, waiting for their turn to board the ferry. Feeling a tugging on the hem of my t-shirt, I looked down to find a child, who waved a stack of lottery tickets in my face. Her mother approached, and I assumed she would point out the obvious problem the girl—that I was a clueless foreigner, and didn’t know how to play the lottery—but she simply motioned to the child, and looked at me with her lips pursed in an insistent frown.

To feign being busy, I turned to browse at the snack stand behind me. Packets of candied fruit, bags of coconut taffy, boxes of dry biscuits; all coated in a thin veneer of red dust from the road. I was grateful I’d had a decent breakfast before leaving Saigon. I had come to Mekong Delta for a number of reasons, but the main reason, I reminded myself ironically, was to eat.

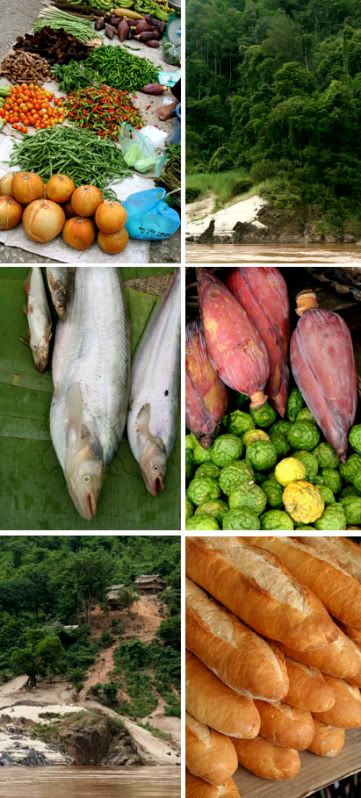

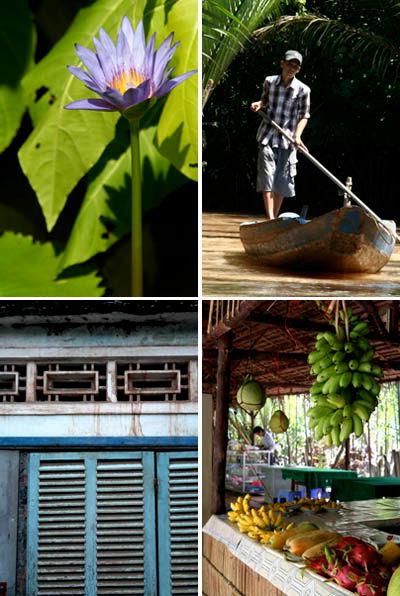

My desire to taste the Mekong Delta had been growing for some time, developing out of a vague collection of cravings into a refined and pressing hunger. It had started, perhaps, when my boyfriend Bordeaux and I first decided to move to Southeast Asia. After some deliberation, we had settled on Saigon as our ultimate destination. In retrospect, it’s hard to say why exactly. Bangkok seemed the more accessible option, but horror stories about the pollution, traffic, and urban chaos put me off. But why Saigon? Really, I knew nothing about the city, or about Vietnam in general. If I’m honest, I’ll admit that it was perhaps the idea of being so near to the Mekong Delta that drew me. Though I had no real knowledge of the river, I had assembled a mental pastiche of images, gleaned from travel brochures and old movies. Images of slim boats drifting over sluggish water through an arcade of palm fronds, and giant catfish sheltered just below the surface. Tropical and mysterious, the qualities that were drawing me to Asia to began with.

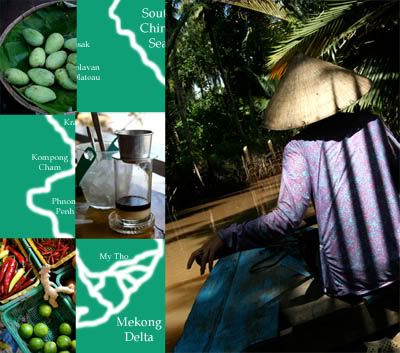

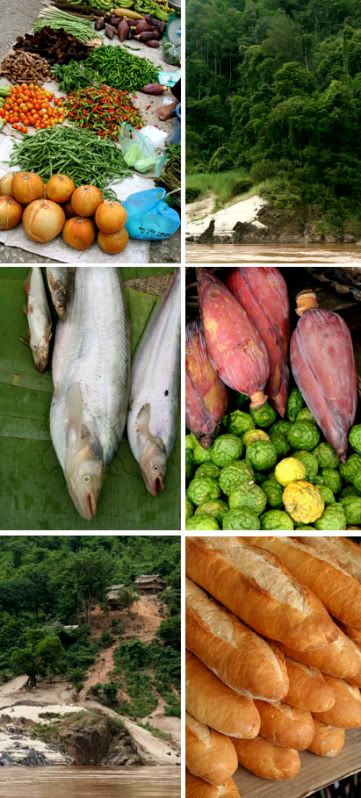

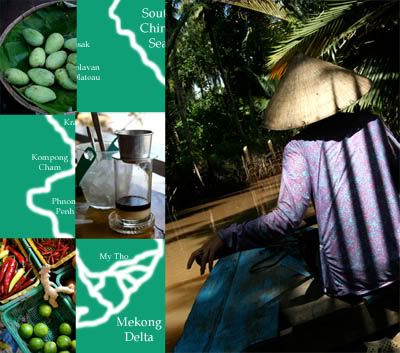

From our arrival in Bangkok to the culmination of our journey, we spent a solid three months traveling. And throughout that time, the Mekong River was a constant guide. We followed it from town to town, drifting downriver at only a slightly slower pace than its muddy brown water. And along the way, we came to know and love how the river tasted. We could feel its richness and fertility in the dripping golden papaya we savored on the banks of Chiang Khong, on the first morning that we saw the river itself; we grasped its salty aquatic flavor in the crisp squares of fried river-weed coated in sesame seeds and dabbed with chili sauce, which we sampled on the promenade in Luang Prabang; and we has tasted its history and culture in the sliver of green mango that garnished a French baguette sandwich in Phnom Penh. But, as close as we came, we didn’t get to taste the river to the end, to the delta.

We made it to Saigon, but only briefly. After only a week in Vietnam, Bordeaux and I boarded a plane and returned to Bangkok. Despite the misguided preconceptions I’d had, we had both turned out to adore the city, and were eager to try living there. So though Vietnam seemed fascinating, we left—never having made it anywhere near the delta. The river’s end remained unseen and untasted, as our plans of living near the Mekong Delta came to an end.

The hunger pangs, however, didn’t end quite so easily. Getting to the delta became a constant goal, a desire I nursed as we lived and traveled throughout the region. And so it happened that over a year later we finally made it there—and I found myself alone, waiting at the ferry port of Ben Tre.

Thankfully, our hotelier returned quickly, and instructed me to climb onto the back of his scooter. We zoomed off, leaving the sun-soaked chaos of the port behind, and slipped into shadow among the leafy gardens of a quiet neighborhood. We passed a string of sugary candy-coloured houses, clacked over a canal on a thin wooden bridge, and twisted into the gate of his guesthouse.

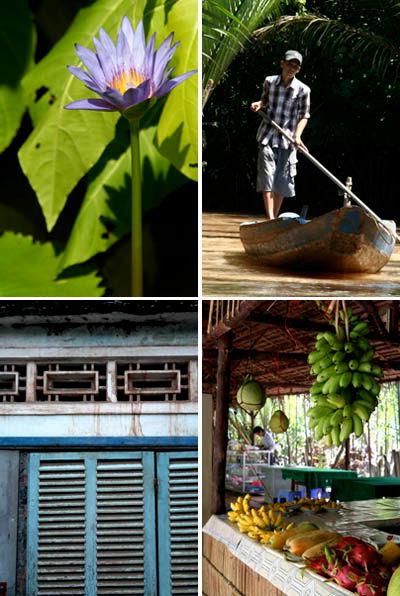

It wasn’t, as I had imagined when I made the booking, a charming boathouse tipped over the river itself, with a hammock slung on the verandah from which I could gaze into the flow of the water. Instead, it was an inland compound of modern mint-green buildings, surrounded by trees. But even though we weren’t on the river itself, there were signs of it everywhere. The air felt sticky with humidity, as if we’d just come on shore after a quick plunge. The garden was flourishing with fruit trees, with pomelos and papaya hanging heavily on straining tree limbs. And a network of shallow streams and canals criss-crossed the yard, giving the feeling that the earth may sink or be swallowed in a flood at any moment. As I climbed off the bike, I found Bordeaux peeking into one of these streams.

“Come, look here.”

All along the bank, there were tiny fish with cartoon eyes, hopping out of the water and onto land. Mudskippers. I’d seen them before in nature documentaries and wildlife books, but they were infinitely stranger in real life. Yet somehow, their amphibious lifestyle seemed to make sense here, where the dividing line between water and earth seemed so thin.

Looking into another patch of murky water, we spied the vague outline of a large fish. It came up to greet us, it’s lips barely breaking the surface of the water. We gazed around the lush garden, continuing our search for wildlife, and spotted a low metal cage partly obscured under some bushes. Looking in, we caught the glimmer of scales on a muscular snake.

“Cobra,” the guesthouse owner informed us. “Maybe you’ll have some for dinner?” We laughed politely, assuming he was joking—though we would later be corrected of this assumption as we looked over the menu for dinner.

We spent the afternoon strolling around town, peeking into coconut candy workshops, being hailed by men wanting us to witness a cockfight, and sipping iced drip coffee in a neighborhood joint. We returned to the guesthouse as the air was cooling down, just in time for dinner. We sat at a table outside, under a pitched canopy of dried palm leaves. After being presented with two icy green bottles of Saigon beer, we were handed a menu, though we had little reason to actually look at it. We’d booked this hotel with a purpose, to eat their specialty dish: elephant ear fish. The fish that had greeted us as we arrived, in fact.

We had only to order and we were immediately summoned to the same stream where we’d had that sighting. Gripping a long net, our waiter scooped into the water, and lifted out a massive silver fish. He dropped it onto the soil, and as it began to make desperate somersaults, commanded me to take a picture. I obligingly took one shot, though I wasn’t eager to document the last undignified moments of my dinner’s life. Satisfied that I’d captured the moment, he grabbed the fish, and disappeared into the kitchen.

When we next saw the fish, it was in a much-altered state. Supported in a wooden frame, it was held upright, and was set on our table with fins splayed, looking almost as if it had swum there itself to join us. Its skin was now more golden than silver, its scales crisp and flaky. It’s tender meat seemed ready to melt away at the first jab of a chopstick. Accompanying it were a bowl of rice noodles, a stack of thin rice paper, and a plate crowded with piles of pineapple, bean sprouts, tomato, and fresh green vegetables and herbs.

I snipped off a morsel of the fish with my chopsticks, layered it on the rice paper, rolled it up, and bit in. The green vegetables tasted sharp, the pineapple exuded an acidic tang, and the well-fried fish was luxuriant fatty. The rice paper contained it all, holding it in for a moment before the flavors revealed themselves on my tongue. I dipped a second piece into the sauce of chili, garlic and fish sauce; it tasted even better.

Over the next week, we crossed the entire delta, and continued our slow tour of Mekong flavors. We rode to the far Western border, past wide grassy expanses dotted with Khmer-style temples and pinnacles of limestone, to slurp on sour spoonfuls of canh chua ca. We rode over the waves to the pristine palm-fringed beaches of Phu Quoc, where we dined on salty caramel-sweet claypot fish. And in every meal, in every dish, and at the bottom of every bowl, we encountered the same flavors. Spicy, tangy, salty, sour, and fresh. The flavors that I had come to know as the taste of the Mekong River itself.

Currently, there is a turkey roasting in our oven, releasing the sharp scent of rosemary into our apartment. Meanwhile, two pumpkin pies are cooling in our kitchen, their smooth golden-orange surfaces flecked with traces of cinnamon, nutmeg, and ground ginger.

Currently, there is a turkey roasting in our oven, releasing the sharp scent of rosemary into our apartment. Meanwhile, two pumpkin pies are cooling in our kitchen, their smooth golden-orange surfaces flecked with traces of cinnamon, nutmeg, and ground ginger. Only after our planning got under way did I realize that this will by my and Bordeaux's first Thanksgiving spent as a married couple. And though I hadn't thought it would matter to me, I'm actually rather glad that we're not just letting the day slip by. We're filling our home with the fragrances of spice, butter, and roasted turkey, and tonight we'll share a staggering meal with our friends. And though I can't say with confidence that I think the pumpkin pie we have for dessert will be 100% perfect, I can at least relax knowing that we'll have lots more Thanksgiving to develop a better one. Which is something to be very thankful for.

Only after our planning got under way did I realize that this will by my and Bordeaux's first Thanksgiving spent as a married couple. And though I hadn't thought it would matter to me, I'm actually rather glad that we're not just letting the day slip by. We're filling our home with the fragrances of spice, butter, and roasted turkey, and tonight we'll share a staggering meal with our friends. And though I can't say with confidence that I think the pumpkin pie we have for dessert will be 100% perfect, I can at least relax knowing that we'll have lots more Thanksgiving to develop a better one. Which is something to be very thankful for.